I must admit that I am sort of an intruder in the Market Research industry. I am not sure if this is the best way to describe myself after 12 years working in an Online Panel Company, occupying different positions in Sales, Marketing and Panel Operations departments. But this is how I feel regarding this profession: a mix of different feelings that go from deep admiration to surprise regarding how some things work in this industry.

One of the things that surprised me more was the questionnaire itself, or better said how researchers ask questions through it. Questions are the basic tools we use to get information from individuals. They are formulated in different ways, mostly depending on the specific type of information to be gathered. There are two different types of information. On the one hand, we have subjective information, such as opinions, emotions, intentions, moods or preferences, that is, all kinds of information that is inside our brains. On the other hand, we have objective information, such as behaviour, that is, all kinds of physical actions for which there might be a trace or record outside the brain of the individual.

Working at an Online Panel Company (Netquest) for more than 10 years I have seen thousands of questions made by hundreds of market research professionals. At the beginning, from a newcomer's point of view, I raised serious doubts on the effectivity of many of the questions I saw. And I am not talking about formal mistakes, such as tendentious questions, biased scales or incomplete answer options. Even many perfectly made up questions raise doubts.

When thinking about questions addressed to get subjective information, doubts are perfectly understandable. Opinions and emotions are volatile data that live deep inside our brains, and it is not easy to capture them without corrupting. The distance between the conscious mind, responsible for answering the questionnaire, and the unconscious mind, the owner of the subjective data, is the main problem to be solved when gathering quality subjective data.

But, what about objective data? It should be easier to access such information. "Facts are facts", I thought. Questionnaires should be effective in accessing objective information. Either I have bought a soft-drink in the last 10 days or I have not. But things are not that easy. People are perfectly aware of relevant facts in their lives (birthdates, a meal with a friend…) but not so aware about activities they commonly do. Unfortunately, Market Research is concerned about many of these common activities, such as purchasing washing powder or watching a specific TV channel on Wednesday at 7 PM.

Do we do what we say we do?

"Ok, questionnaires are not perfect tools” told me a professional, “but, which is the alternative?" It is true: questionnaire is a wonderful tool that has been providing helpful insights for researchers during more than 100 years, with unparalleled value for money.

But now we are entering a new era and we need to rethink almost everything we do. Is still the questionnaire effective in the digital era? Can we keep on investigating the digital consumer with the same tools we have been using, with little changes, for the last 100 years?

This was the question that led us to develop a research project that was presented in the latest ESOMAR WORLD event (Dublin, September). We decided to focus on objective data, given that we have now a tool that can be used instead of the questionnaire to register online behaviors: the tracker, a piece of software that, once installed in the browsing devices (PCs, smartphones and tablets) of the members of a panel, provides data regarding visited websites, app usage and digital ad exposure. As these panel members are also committed to participate in surveys, the comparison between tools (the surveys and the tracker) was possible. It was a unique opportunity to compare what people say to what people do.

Results of the experiment

We expected to find differences between both types of data, but… results overcame our expectations.

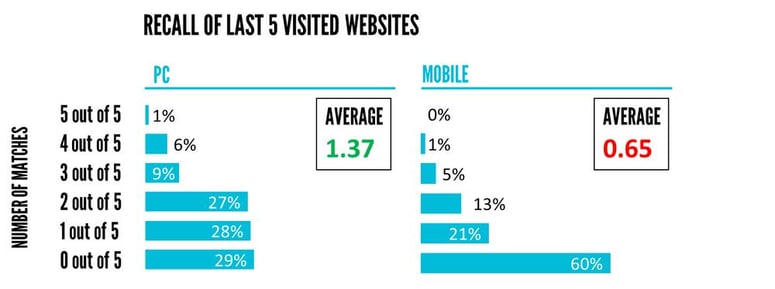

When asking people about their last 5 visited websites (just before accessing the survey), only 1% of respondents was able to properly recall 5 of 5 websites. 84% of the sample could not recall properly more than 2 websites. This result is quite shocking: if we are not able to recall websites that we have just visited, how can we expect people to recall more distant and complex activities?

Contrary to what we expected, people performed better in recalling long term activities (recall in the last 2 months) than short term ones (in the last 7 days).

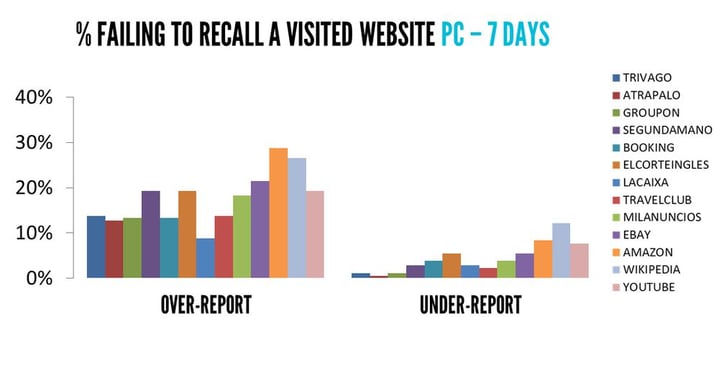

But, which is the origin of the mismatches? Are people declaring to visit websites that they did not actually visit (over-reporting) or, on the contrary, are people failing to recall websites they visited (under-reported)? To our surprise, people were clearly prone to over-report their online activity.

The explanation of this result could be related to the well-known “yes-saying” effect. People, when are in doubt, tend to answer affirmatively. It is something strange, but repeatedly observed in many researches. Daniel Gilbert, author of “Stumbling on Happiness”, suggests a possible explanation for this effect. Gilbert proposed that understanding a statement must begin with an attempt to believe it. This may produce a bias toward positive answers. Again, in our experiment this effect was attenuated when asking about long time periods (2 months).

The explanation of this result could be related to the well-known “yes-saying” effect. People, when are in doubt, tend to answer affirmatively. It is something strange, but repeatedly observed in many researches. Daniel Gilbert, author of “Stumbling on Happiness”, suggests a possible explanation for this effect. Gilbert proposed that understanding a statement must begin with an attempt to believe it. This may produce a bias toward positive answers. Again, in our experiment this effect was attenuated when asking about long time periods (2 months).

Till this point, we could summarize the following findings:

- People perform poorly when remembering online activities.

- Fewer mismatches are observed for longer periods of time in spontaneous recall.

- People are more prone to over-report, especially in short time periods.

The worst is yet to come

And what about the future? I guess you will agree that the future is mobile, so the same analysis implemented for PC users was done for smartphones users. And the results were clear: people perform even worse in recalling last visits in their mobile devices. 60% of mobile respondents could not recall correctly a single website. So yes, it seems the worst is yet to come …

What we have learned

In light of this experiment, one may be tempted to augur a dark future for the questionnaire: it seems unsuitable for collecting objective data on digital behaviors, especially those that take place in the mobile world. And let’s be realistic: our lives are happening mostly online, and increasingly mobile.

So what can we expect for our old friend, the questionnaire? My guess is a good future. If I were forced to bet on it, I would predict an increase in the use of the questionnaire. The amount of problems to investigate is growing. With the emergence of each new source of observational data, such as social media listening and other sources of Big Data, new reasons to make surveys appear. So many “whats” require answering many “whys” and the questionnaire keeps holding a privileged position when it comes to understanding the reason why people behave like they do.

Of course, things will never be that easy again. The time when we could use a questionnaire to solve almost any research problem (any type of data) has gone. Today’s consumer must be studied from several points of view, through diverse methods and data sources that jointly compose an integrated picture. I am sorry, researchers: your job has become more complex than it was never before, but more exciting as well.

As published in http://www.marktforschung.de/hintergruende/themendossiers/big-data/dossier/the-times-they-are-a-changin-for-the-questionnaire/

Results from an experimental study that compares what people do with what they say they do regarding their online behaviour.