How many people have actually been infected by COVID-19? Over the past few weeks we've seen a surprising range of conflicting figures. Surprising both because of the simplicity of the question and the difficulty of getting an answer.

In the information age, at a time in human history when we have more diagnostic tools and data sources than ever, we are failing to answer this simple but crucial question, as we will see further on. Fortunately, there is a way to provide an answer using a tried and tested method: the sample.

The official figures are unrealistic

Governments have been reporting the figures of infected people since the beginning of the crisis. However, it soon became clear that these figures were clearly lower than reality, for a number of reasons:

1. Asymptomatic patients: infected people with no symptoms, who are or have been infected. Without symptoms, no tests are carried out.

2. Lacking the capacity to carry out enough diagnostic tests. While countries like Germany have been able to carry out large-scale testing, other countries like Spain or Italy have not been able to test as many people as they would have liked. Their recommendations have therefore been for patients with symptoms to stay at home, without testing to see whether or not they have been infected.

The main piece of evidence that the official infection data is incorrect are the disproportionate deaths in comparison to infection figures. Using Spain as an example, on 20 April there were 200,210 infected patients with 20,852 deaths, a rate of 10.4%. We know that COVID-19 does not have such a high mortality rate, which can only mean that the number of infected people is much higher than the reported number.

Statistical estimates

Several people used statistical models to attempt to estimate the real number of people infected and to try and warn us about the coming situation.

As early as 10 March, authors such as Tomás Pueyo warned governments around the world about the gravity of the situation. Simply by reviewing (1) the existing data, (2) the experience of the countries that were the most affected at the time (China, South Korea, Italy and Iran) and (3) knowledge about the usual exponential growth of viral infections, Pueyo predicted the grim panorama that awaited us, especially if governments did not put isolation measures in place.

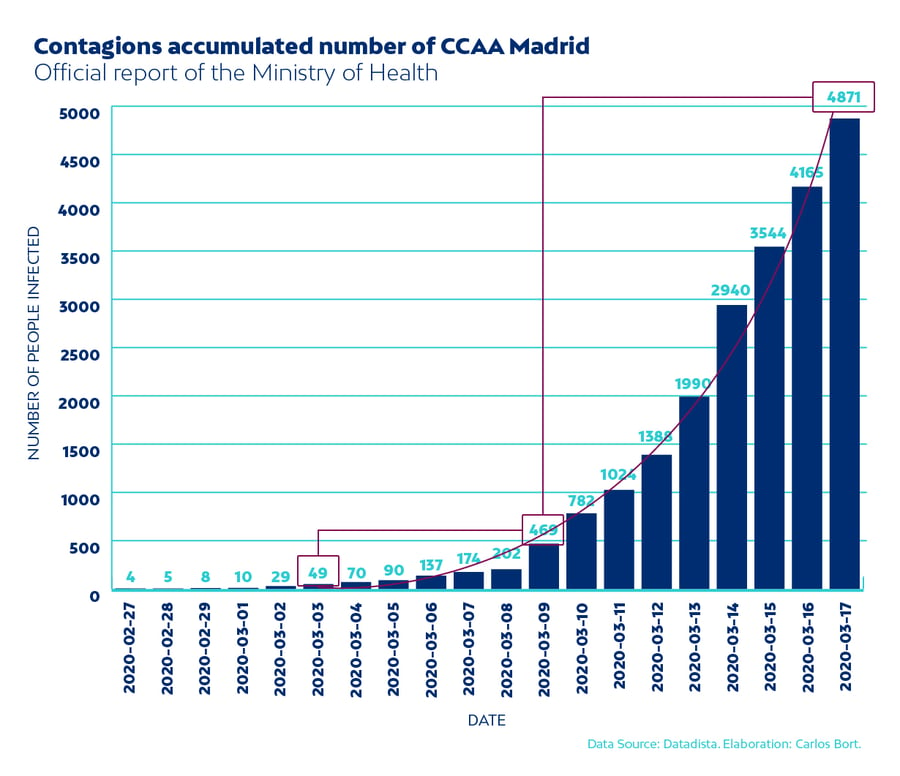

Other authors, such as former Netquest colleague Carlos Bort, dared to make further estimates, claiming that the number of actual infections on 17 March in Madrid (Spain) could be up to 100 times the reported figure. These estimates are made by modelling the different stages of the disease (infection, incubation, symptomatic or asymptomatic, recovery or death) and the average period of time between each stage.

In his article, Bort made one estimate based on the official number of people infected, and another based on the number of deaths. The main disadvantage of the first estimate was the unreliability of the official data, which weakened the analysis. On the other hand, the estimate based on the number of deaths was much more reliable. Unfortunately, we later discovered that even the death figures were unreliable, as deaths caused by COVID-19 had not been properly counted for several weeks, especially in nursing homes.

On 31 March, Imperial College London further hypothesised that the level of infection was much higher than official figures, putting the number of infected people in Spain at 7 million (15% of the population). At that time, the figure of 7 million people was 100 times the official number, in line with Bort's estimate.

All these estimates are clearly more realistic than the official government-provided data, but they still suffer from a fundamental problem: a lack of reliable data to work from.

This is where classic sampling comes to the rescue again.

Nonetheless, it’s still paradoxical. We are used to hearing that, in the era of Big Data, information is abundant, freely available and that it is possible to estimate anything using the right methods.

Well, that's simply not true. If we are to reliably estimate the real number of people infected by COVID-19, we need a representative sample. Yes, a sample, the same tool we use for election surveys and brand recall tests.

If it has been properly designed, a sample can allow us to accurately estimate the real impact of a disease in the population, regardless of factors such as symptomatology or how saturated the hospital system is. The principle is very basic: people are selected at random and a test is carried out to detect the disease. People are chosen for the sample regardless of whether or not they have symptoms, the region they are from, or their age... and the result is then extrapolated to the entire population.

The Spanish Ministry of Health has already started conducting a study that aims to estimate the percentage of the population that has been infected, whether or not they are ill right now, through a large sample of 90,000 people distributed across 2 waves. The people chosen for the sample will be given a rapid antibody test, which shows whether or not someone has already had the disease thanks to the trace it leaves in the immune system. Since the rapid tests are not very reliable, those who test negative will be subject to a second test (the famous PCR test), which is much more reliable.

Only public bodies have the capacity to carry out this type of study using a truly probabilistic sample, since, as has been explained on numerous occasions, this requires having a list of the entire of study universe (in this case, the entire population of Spain), the means to access them and the power to make them participate.

Things to keep in mind with regard to this sample

I don’t know the exact method the public body is using to study the extent of the spread of the virus, but the following options were probably considered:

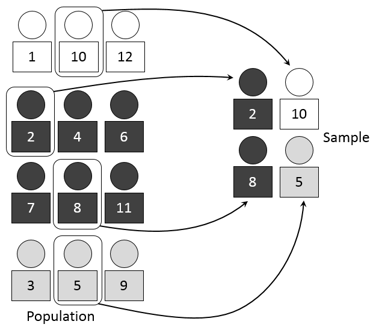

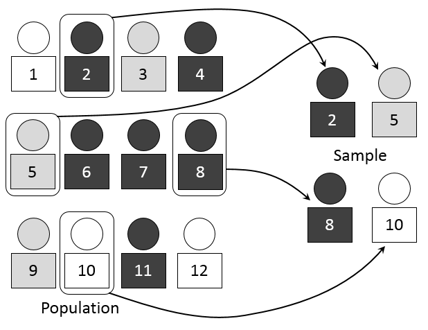

1. They could use simple random sampling. This would be like putting raffle tickets in an urn, with each ticket representing one inhabitant, then drawing 60,000 random tickets. I wouldn’t recommend this for one reason: the virus infection rate is very unequally distributed across regions, and even varies from town to town and in different neighbourhoods. This can be used to our advantage to design a more efficient sample (see the paragraph below).

2. They could use stratified sampling. This technique divides the population into groups, known as strata, and ensures that the sample includes a fixed number of people from each stratum. In the case at hand, the most logical option would be to use geographical strata (Autonomous Communities or provinces), but age groups, social class or a combination of these factors could also be used. Stratified sampling reduces the level of error. And in studies like this, it would be possible to allocate more of the sample to regions that we know have been more affected, in order to get better estimates.

3. Finally, it is possible to combine stratified sampling with cluster sampling. In this case, it would be advisable to choose families as a sampling unit: a medical team will have to collect samples from a household, so it would be better to get samples from all the members of that household.

Importance of the study and alternatives

The randomised study proposed by the health authorities is vitally important. Even if the short-term health crisis (hospital saturation) is under control, knowing what percentage of the population has been infected is crucial to determine our current herd immunity level. If more people have been infected, that means a higher population has immunity from the disease, and they will act as natural barriers to stop the spread of the virus, protecting the uninfected. Using this information and knowledge of how the virus is transmitted, epidemiologists can determine when the population has herd immunity, which will allow confinement measures—which have had such an impact on people's lives and the economy—to be lifted.

It goes without saying that the study proposed by the Ministry is very costly and can only be carried out by an official body. But even a sample that is not strictly random could offer estimates much closer to reality than the official figures we currently have. Netquest has an online panel with the capacity to survey more than 80,000 people in Spain or Brazil, who are willing to take part in a study of this kind. The first phase could simply be finding out if these people have had symptoms, even if they have not been tested. But it would also be possible to send participants a kit to collect a sample themselves and send it by courier (assuming it is possible to send the samples by courier without this affecting their subsequent analysis, and assuming that participants could reliably obtain a sample themselves).

On many occasions, getting information with an adequate level of precision quickly is preferable to perfect information that arrives late, or the total absence of reliable information—which has been the case until now. Decision-making is very sensitive to delays. However, it looks like the sample study in Spain will still take some time to arrive due to logistical problems.